Aquatic Monitoring Programs

Turning monitoring data into defensible knowledge, decisions, and action

Aquatic monitoring programs are the backbone of fisheries and watershed management. They provide the empirical evidence needed to understand system status, detect change, evaluate risk, and assess the effectiveness of management and restoration actions. These programs operate across multiple jurisdictions and mandates, including federal and provincial governments, Indigenous Nations, watershed groups, and non-profit organizations.

Monitoring programs typically focus on one or more components of aquatic ecosystems, including:

- Water quality (e.g., pH, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, nutrients, metals)

- Water quantity (stage, discharge, peak flows, low flows, etc.)

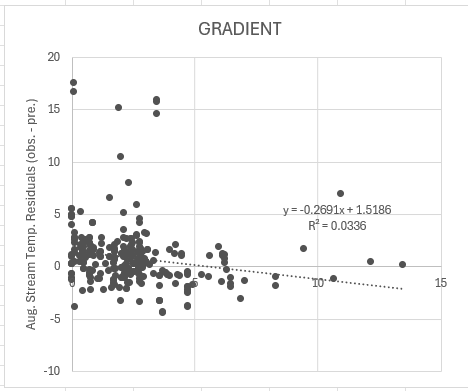

- Stream temperature (temperature extremes, growing seasons, and associated actions and effects)

- Benthic invertebrates (diversity, abundance, densities etc.)

- Fish abundance, distribution, and life-history expression

- Fish habitat condition and connectivity

While these programs generate large volumes of valuable data, they are often challenged by fragmented systems, inconsistent data structures, limited analytical capacities, and weak linkages between monitoring results and our collective understanding of aquatic ecosystem health.

Our role is to help bring these components together.

How We Support Aquatic Monitoring Programs

We support aquatic monitoring programs by designing integrated systems that link field data collection, quality control, analysis, modelling, and communication. This includes building custom databases and web tools, developing field-ready workflows, installing or integrating sensor networks, and ensuring monitoring data can be directly used in assessments and models.

Where Monitoring Connects to Other Service Areas

Life Cycle Modelling

Aquatic monitoring data are essential inputs to life cycle models, particularly for identifying limiting factors and evaluating cumulative effects.

Examples include:

- Using stream temperature and discharge time series to modify life stage-specific survival or capacity within trout/salmon life cycle models

- Linking water quality monitoring (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, dissolved oxygen) to stressor–response relationships that affect reproduction or early life-stage survival

- Using fish abundance or productivity monitoring to calibrate and validate model outputs and test alternative scenarios

Monitoring data allow life cycle models to move beyond theoretical exercises and become decision-relevant tools grounded in observed conditions.

Hydrological and Hydraulic Modelling

Monitoring programs provide the empirical basis for hydrological and hydraulic analyses.

Examples include:

- Using hydrometric data to develop, calibrate, and validate flow models in gauged and ungauged basins

- Integrating continuous stage–discharge records into habitat suitability or environmental flow assessments

- Combining flow and temperature monitoring with climate or land-use scenarios to assess future risk to fish and habitat

- Supporting hydrodynamic modelling by anchoring simulated velocities and depths to observed flow conditions

Without (some) defensible monitoring data, even the most sophisticated hydrological models are of limited value.

Custom Web Tools and Databases

Modern aquatic monitoring programs increasingly rely on digital infrastructure to remain efficient, transparent, and adaptive.

We routinely develop:

- Centralized monitoring databases (PostgreSQL/PostGIS) that store time-series data, metadata, QA/QC flags, and spatial context

- Web-based dashboards for near-real-time visualization of flow, temperature, and water-quality data

- Field data entry tools and lightweight applications that reduce transcription errors and improve data consistency

- Program-specific portals that allow managers, partners, and communities to explore monitoring results without requiring technical software

These tools allow monitoring programs to shift from static spreadsheets toward living systems that evolve with program needs.

Watershed Assessments and Cumulative Effects

Monitoring programs are essential for grounding watershed assessments in reality and tracking change over time.

Examples include:

- Using monitoring indicators to assess watershed condition relative to benchmarks and thresholds (e.g., riparian assessments; stream habitat surveys)

- Supporting cumulative effects assessments by linking spatial indicators (e.g., land use, disturbance) to observed hydrologic and biological responses

- Informing risk-based decision-making by identifying trends, early warning signals, and uncertainty

- Enabling adaptive management, where monitoring results directly inform revisions to objectives, strategies, and actions

In this context, monitoring is not just data collection, it is the feedback loop that keeps management strategies honest and understandable.

From Data Collection to Stewardship Outcomes

Well-designed aquatic monitoring programs do more than satisfy reporting requirements. When integrated with modelling, assessment frameworks, and modern digital tools, they become powerful assets that support:

- Defensible decision-making under uncertainty

- Transparent communication with communities and partners

- Evaluation of restoration effectiveness

- Long-term stewardship of fish and aquatic ecosystems

My work focuses on ensuring monitoring programs are fit-for-purpose, scalable, and directly connected to the decisions they are meant to inform, turning raw data into insight, and insight into action.